The Critical Nature of Identifying Tooth Cracks

Tooth fractures are more than just a common dental issue; they are a potential threat to dental health that can lead to serious complications if not properly managed. Recognizing these fractures early on is essential for preventing further damage and ensuring effective treatment. This article aims to equip dental professionals with the knowledge to identify and address different types of tooth fractures promptly.

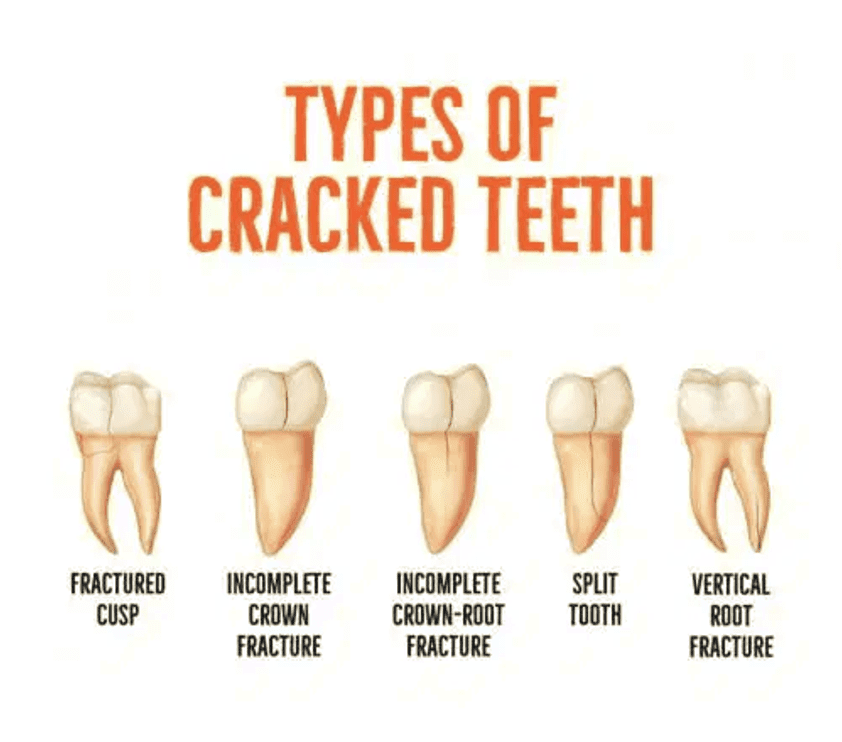

Overview of Cracked Teeth

Tooth cracks can vary widely in type, severity, and symptoms. They often result from trauma, biting on hard objects, or significant temperature changes. Understanding the general characteristics of these fractures helps in making accurate diagnoses and choosing the best treatment plans

Type 1: Craze Lines

Craze lines are tiny cracks that affect only the enamel. They are often harmless and usually do not require treatment other than for aesthetic reasons. These superficial fractures are more common in adults and can be seen as fine lines on the surface of the teeth. Dentists can diagnose craze lines through careful visual examination and by using techniques like transillumination, which highlights the fractures by passing light through the tooth.

Type 2: Fractured Cusp

A fractured cusp occurs when a part of the tooth’s crown breaks off completely or partially, extending below the gum line. The severity can vary, with the lingual cusps of lower molars and the buccal cusps of upper molars being the most prone to this issue.

These fractures typically begin at the occlusal surface and progress downward along either a buccal or lingual groove and the mesial or distal marginal ridge. Significant contributing factors include occlusal trauma and force, as well as existing restorations that weaken the cusps.

In some cases, a traumatic event can cause the fractured cusp to detach completely, leaving a segment that may still be attached to the gum tissue, necessitating removal. The exposed tooth area may be sensitive to temperature until it is properly restored. Patients might also experience discomfort when biting or sensitivity to temperature before the cusp fractures completely, usually feeling pain when applying or releasing biting pressure. This pain typically subsides once the fractured cusp is removed.

To identify a fractured cusp, transillumination can be useful, as the light will not pass through the fractured part of the tooth. The prognosis for retaining the tooth is generally good, although severe cases may require root canal therapy or crown lengthening. Early symptoms of cusp fractures should be addressed with cuspal coverage like crowns or onlays to prevent further damage.

To maintain tooth integrity and prevent fractures from worsening, using crowns or onlays is recommended, along with regular monitoring of the patient’s condition over time.

Type 3: Cracked Tooth

A cracked tooth is characterized by an incomplete fracture starting from the crown and extending below the gum line, usually in a mesial-distal direction. This crack can pass through one or both proximal surfaces, with its vertical depth varying significantly.

The crack might remain confined to the tooth’s crown or extend vertically into the root. Unlike a fractured cusp, a cracked tooth tends to be more centrally located occlusally and can progress downward, increasing the risk of pulpal and periapical complications.

Determining the crack’s location and extent can be challenging. Some cracks are visible with magnification or due to bacterial staining, while others are identified with a dental explorer because they cause a noticeable separation of the enamel. However, the visible surface crack doesn’t always indicate the extent of the apical crack. Patient symptoms also vary; some may experience temperature sensitivity or pain when biting, while others might have no symptoms.

Excessive occlusal forces and weakened tooth structures from existing restorations contribute to the formation of cracks. Undermined cusps and marginal ridges also create conditions conducive to cracking. Removing old restorations is advisable to assess the crack’s depth and extent.

Various diagnostic tests can help identify cracked teeth. Removing old restorations is a starting point, and magnification is crucial for evaluating the crack. The crack may be seen extending along the pulpal floor from mesial to distal. Extending the pulpal floor to follow the crack apically provides information on depth and proximity to the nerve.

If the crack extends into the interproximal area, a perio probe can check for a narrow band of bone loss along the root, indicating a root fracture. Techniques like tooth staining, transillumination, or wedging can help assess the crack’s extent. Pulp vitality and patient symptoms also aid in determining the severity of the crack. The extent and symptoms of tooth cracks are highly variable.

Treatment for a cracked tooth depends on the crack’s extent, the dentist’s experience and judgment, and patient symptoms. There are no definitive restorative recommendations in the literature for treating cracked teeth. Proper diagnosis and preventive strategies are crucial.

Root canal treatment may be necessary if pulpal and periapical symptoms are present. However, treatment might be as minimal as replacing a direct restoration to providing full or partial cuspal coverage. The dentist must decide the appropriate treatment based on the crack’s extent, depth, and the tooth’s remaining structural integrity. The prognosis for a cracked tooth is always uncertain, as cracks can progress even with cuspal coverage. Limiting tooth flexure with bite adjustment and cuspal protection is essential.

Despite preventive measures, micro-movement during tooth function can propagate cracks over time. Not all cracked teeth will fail, but their fate depends on patient circumstances, occlusal stability, and cooperation. Preventive strategies include eliminating damaging habits, such as using a night guard to control bruxism, providing cuspal coverage, and counseling patients about the variable outcomes of cracked tooth treatment. Patients should be informed about the uncertain prognosis of cracked teeth.

Type 4: Split Tooth

A split tooth is identified as a crack that extends through the entire tooth, segmenting it into two distinct parts. This type of fracture often results from the long-term progression of an untreated cracked tooth. The treatment typically involves extraction of the tooth because restoration is not feasible. Preventive measures include early intervention for cracked teeth and protective coverings like crowns.

Type 5: Vertical Root Fracture

Vertical root fractures are cracks that begin at the root and move upwards. They are often related to previously treated root canals and are notoriously difficult to detect and treat. Symptoms may include pain and swelling. Treatment usually involves extraction of the affected tooth due to the poor prognosis for repair.

Advanced Diagnostic Techniques for Tooth Fractures

Advancements in dental technology, such as high-definition x-rays and 3D imaging, have greatly improved the diagnosis of tooth fractures. Regular dental check-ups and imaging can help catch fractures before they become severe, greatly improving outcomes for patients.

Preventing Tooth Fractures: Best Practices

Preventive care is key in avoiding tooth fractures. Recommendations include using mouthguards during sports or sleeping, avoiding chewing on hard objects like ice or hard candy, and addressing bruxism or other parafunctional habits. Regular dental visits allow for early detection and management of minor fractures before they evolve into more serious problems.

Learn to Handle All Types of Tooth Cracks With IDEA

Through meticulous training and adherence to rigorous standards, our academy ensures that every graduate is capable of meeting the highest expectations for functionality and aesthetics after taking our Posterior Course with Didier Dietschi, D.M.D., Ph.D.